-

ABOUT

Marcelo López-Dinardi is an Associate Professor of architecture at Texas A&M University. His work explores architecture’s entanglements with culture. He is the editor of Architecture from Public to Commons (Routledge, 2023) and Degrowth (ARQ, 2022), and co-editor of Promiscuous Encounters (GSAPP Books, 2013). López-Dinardi’s words and works have been featured in the JUMEX Museum, MoCAD, Istanbul Design Biennial, Citygroup, Storefront for Art and Architecture, Old Armory of the Spanish Navy of Puerto Rico’s National Gallery, MAC-PR, CAAPPR, The Avery Review, The Architect’s Newspaper, Domus, Art Forum, URBAN_NEXT, PLAT, ARQ, Materia, and Bitácora Arquitectura. López-Dinardi is 2025-26 TAMU Melbern G. Glasscock Humanities Research Center Fellow elected to…

-

CEMENTED DREAMS ON RADIO

I was interviewed about my ongoing project CEMENTED DREAMS for the radio program Arquitectura HOY (Architecture Today) hosted by architect Elliot Santos at WIPR, the radio station of the University of Puerto Rico. In the hour-long conversation I introduce the various themes surrounding the development of the cement industry in Puerto Rico and its unfolding as a cultural agent until today. You can listen to the recorded conversation, in Spanish only, here.

-

THE EXPANDED GALLERY

“The Expanded Gallery” (also “La galería expandida”) is a text, book chapter that discusses the life of Mexico’s City curatorial platform Proyector in the book Proyecciones, published by Arquine, 2025. “Proyector is a curatorial platform based in Mexico City, dedicated to promoting emerging voices in contemporary architectural research. Proyector is committed to fostering new strategies and critical, theoretical and historical tools on spatial issues. During the three seasons of the annual program, researchers (and research groups) are invited to work together with the curatorial team of Proyector in a collaborative manner, seeking the projection of their research in multiple formats:…

-

ARCHITECTURE’S SEARCH FOR COMMONING

“Architecture’s Search for Commoning” is a text, book chapter contribution to Architecture as Commoning Practices Edited by Architensions (ZicZic, 2025) that discuss current approaches of design practices engaging with the concept of the commons. From the editors, “The book presents Architensions’ research, reframing the notion of the commons and the collective from a transdisciplinary lens, examining how commoning practices shape the urban fabric and the spaces of the built environment. The book takes the small town of San Ferdinando, Calabria, in Italy, as a case study, addressing contemporary issues of equity, climate, and labor through a vision plan that guides…

-

ADDRESSES 1978-PRESENT

Selected contribution to PATIO Magazine issue on Identities, 2025. Addresses 1978-present visualizes the lived addresses location of a 46 year old person who has moved more than thirty times across the Americas and the Caribbean. In doing so, this work seeks to find defining principles in the locations of a given geographical identity. Are identities tied to location? Are identities geographical? By collecting the addresses in text form, akin to a physical curriculum vitae (CV), and visualizing them using Google Maps tools, this work intends to neutralize the charged nature of moving, displacement, and the constant cycle of new beginnings…

-

ECOLOGIES OF THE MACHINE: EXHIBITION REVIEW

My review of the exhibition, Ecologies of the Machine: Landscapes of Cement and Power, led by Erika Loana and Kim Förster with Tania Tovar from the gallery Proyector in Mexico City is out in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. Link here.

-

TENTH STREET EXHIBITION

The Tenth Street Historic District Freedman’s Town is one of the few Landmark Historic Districts that remains in place in Texas and the nation. However, since its designation as a National Register of Historic Places in 1994, it has undergone intense demolition provoked by a lack of municipal oversight and resources in a historically neglected neighborhood. The work in this exhibition highlights an effort led by Texas Target Communities of Texas A&M University, Tenth Street Community members, and a large group of architecture students and faculty who engaged with the neighborhood in the Spring of 2024. The projects presented here…

-

COMMONING POLICIES

Commoning Policies was a conversation between Pilar Finuccio of the CUP, Damon Rich from HECTOR urban design and myself as part of KoozArch’s New Rules for School series. Read the exchange here.

-

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR – TENURE

Elated to share that I have been promoted to Associate Professor with Tenure in the Department of Architecture at Texas A&M University. Come visit!

-

WORKSHOP–TALK UDLA SANTIAGO

In April I had the fortune of visiting Santiago, Chile, to lead a Workshop with thesis students at the Universidad de las Américas, and to do a book launch with contributors Linda Schilling Cuellar and Fernando Portal.

-

READING ARCHITECTURE FROM PUBLIC TO COMMONS at CITYGROUP

The exhibition, Reading Architecture from Public to Commons, opens up the homonymous book to expose its contents visually, offering an opportunity for a first read that extends the connections of the printed document and creates a physical space for additional interpretation. Highlighting and complementing textual excerpts with imagery, the exhibition invites viewers to scroll through the contents-manually, in a situation distinct from the linear act of reading, to extend, link, or even rethink the book’s original ideas. The exhibition highlights the words and work of Pelin Tan, Amira Hanafi, Marina Otero Verzier, Fernando Portal, Nandini Bagchee, coopia, Emanuel Admassu, Luciana…

-

BRIDGING THE DIVIDES, POST-DISASTER FUTURES FELLOWSHIP

Elated to have been selected as a fellow for Bridging the Divides: Post-Disaster Futures study group. Bridging the Divides is “a program funded by a 1.2-million-dollar Mellon grant that was awarded to CENTRO, The Center for Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College-CUNY, to support the establishment of collaborative, interdisciplinary study groups composed of artists, scholars, and journalists from across Puerto Rico and its diasporas.” In its second iteration, “the second group, which focuses on the theme of Post-Disaster Futures, is now hosted at Princeton University and led by current Princeton Professor Dr. Yarimar Bonilla and Dr. Deepak Lamba-Nieves, who is…

-

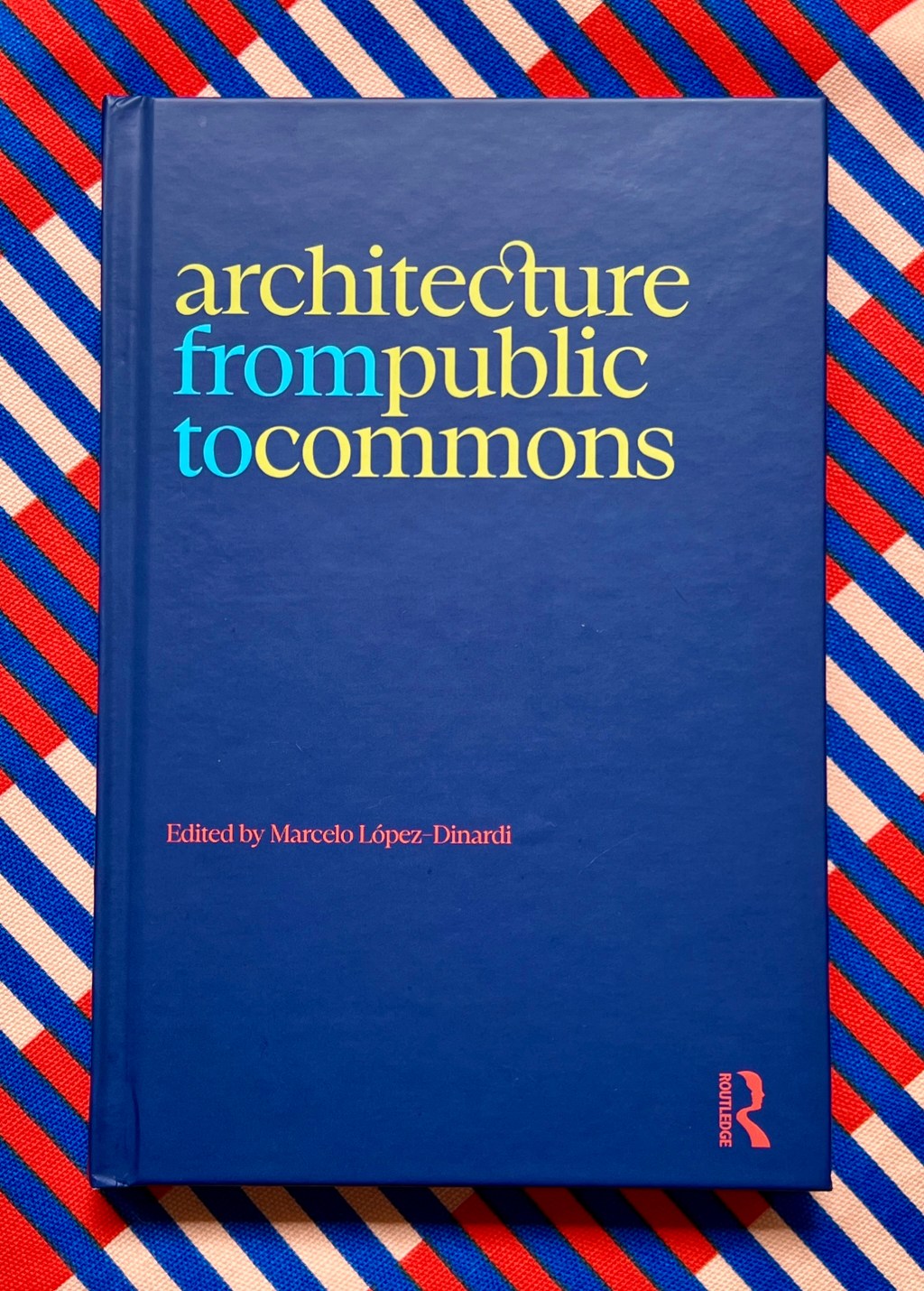

BOOK: ARCHITECTURE FROM PUBLIC TO COMMONS

Incredibly happy to share Architecture from Public to Commons. The book provides an urgent framework and collective reflection on understanding how to reconsider and recast architecture within ideas and politics of the commons and practices of commoning. Architecture from Public to Commons opens a dialogue with the scales of the commons, the limits of language for fluid identities, the practices of architecture as an institution, the design of objects for shared value, land protocols that explore alternatives to profit-seeking, and spirited conversations about revolting against architectural labor. Specific chapters also explore the boundaries of Blackness across the Atlantic, water cycles…

-

MUSEOS EN COMÚN – MUSEUMS IN COMMON at JUMEX

In October I was fortunate to participate in the Lugares Comunes (Common Places) panel as speaker as part of the exhibition Museos en Común (Museusm in Common) organized by Marielsa Castro at the JUMEX Museum in Mexico City. Ler more about the fantastic exhibition project here.

-

BOOK CONTRIBUTION – TDTA

The books for the TEATRO DELLA TERRA ALIENATA winning pavilion at the 2019 Triennale di Milano arrived in English and Spanish and I am happy to have contributed with a roundtable discussion. You can obtain the books here.

-

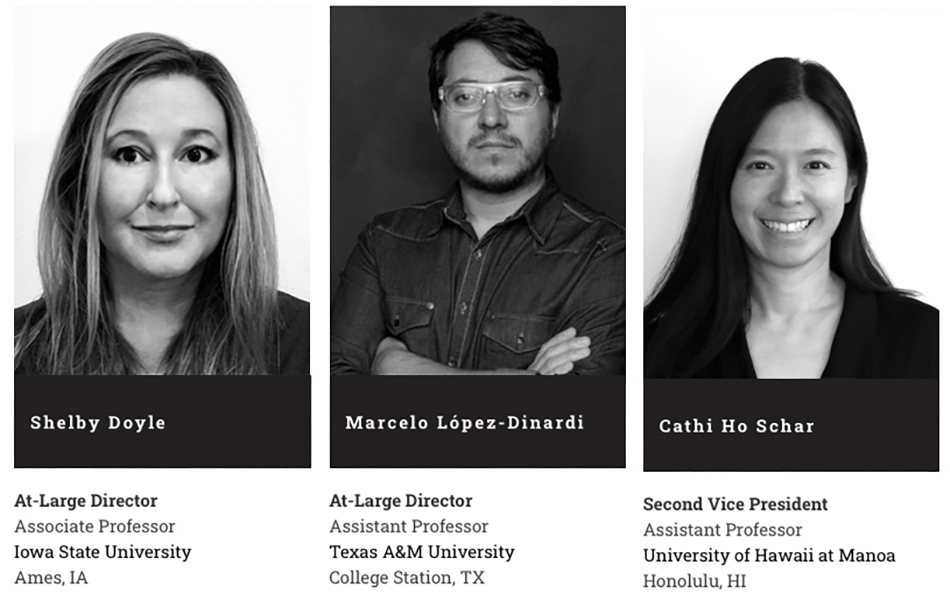

ACSA At-Large Director

Happy to have been elected to an Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) At-Large Director and will serve in its Board of Directors starting July 2022. More info here.

-

FORMS OF ENGAGEMENT

Interview with PLAT journal editors discussing forms of engagement, care, architecture education, and architecture as potential. Visit their website here.

-

MAKING THE PUBLIC–COMMONS

MAKING THE PUBLIC–COMMONS was an installation and a conversations-marathon project motivated by the ambition and need to elaborate our positions towards the making and building public–commons, primarily through an act of appearance and conversation much required in our cultural context. The project relied mainly on direct dialogue and embodied engagement. It proposed dialogue and conversations around topics of—but not limited to, how and what constitutes the public and the commons, and: institutions, commoning, landscapes, justice, measures, cooperation, water, ecologies, language, and appearance. Guests included Marina Otero Verzier, Pelin Tan, Elise Hunchuck, Bryan Lee Jr., AD-WO (Emanuel Admassu, Jen Wood), COOPIA…

-

TABLE 21-8

-

DIGITAL BOOK: AN AGENDA FOR BCS

As a newcomer faculty to Texas in the Fall of 2018, I decided to dedicate most of my architecture studios—junior, senior, and graduate, to learn about the cities of Bryan and College Station (BCS), their logic, motivations, and potential pitfalls. These studios were a new endeavor to many. The thinking of architecture as a cultural product in dialogue with territorial complexities has been the driving force to these research-based studios. We carefully considered, investigated, pondered, and visualized the multiplicity of factors that we understood are shaping the cities. We did this primarily through mapping. There are tens of information and…

-

QUESTIONS FOR DOWNTOWN BRYAN, TX

QUESTIONS FOR DOWNTOWN BRYAN, TX is a collaboration with MILM2 long-standing Proyecto Pregunta (or Question Project) for their latest book of urgent questions. For this occasion I asked WHAT HISTORY MEETS COMMUNITY? in response to the city’s revitalization slogan Where history meets community; and WHY THE CITY IS STILL SEGREGATED? to acknowledge the historical and continuing divide of the “historic” downtown with the African American communities in the North portion of also “historical” part of town. Project in collaboration with Tyrene Calvesbert.

-

ARCHIVAL IMPRESSION: (RE)COLLECTING GORDON MATTA-CLARK

This article examines the contested relationship between the artist Gordon Matta-Clark, who was educated as an architect, and his father, the Surrealist painter Roberto Matta, with regards to architecture and the archive. It argues that architecture was impressed, archived in Matta-Clark not only by his father, but also by his destructive drive and the reinscription of his work in his collection at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal in 2002. It discusses what it means to archive Matta-Clark’s personal architectural dimension, in light of Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever, and to collect his work in an architecture-centric institution. Bitácora Arquitectura #45…

-

BRIDGING THE BINATIONAL CITIES OF LAREDO AND NUEVO LAREDO

ARCHITECTURE MATTERS: BRIDGING THE BI-NATIONAL CITIES OF LAREDO AND NUEVO LAREDO The studio explores questions of political boundaries and their spatial implications in the bi-national cities of Laredo (US) and Nuevo Laredo (MX). The studio research and considers the existing conditions as they relate to questions of ecology, trade, migration, culture, among others. The last few weeks students were asked to propose strategies as a design response, this is, how to construct forms of engagement with the sites and questions—at regional, urban or small scale design interventions. More than fully resolved projects, the studio focuses on conceptualizing the responses and…

-

EXIT INTERVIEW: MUSINGS, HISTORIES, IDEAS

This remote-teaching studio takes the idea of an academic “Exit Interview” to develop a dialogue, discussions—or musings about contemporary architectural culture theories-and-practices, its production politics, its purpose, formulations, capacities, limits, and motivations. In brief, what is a project in architecture? It focuses primarily on architectural production of the last fifty years. Since this summer studio is the last in the undergraduate sequence, we will explore through active “debates and interviews,” the ideas, voids, and opportunities of the education that students have completed up to this point.

-

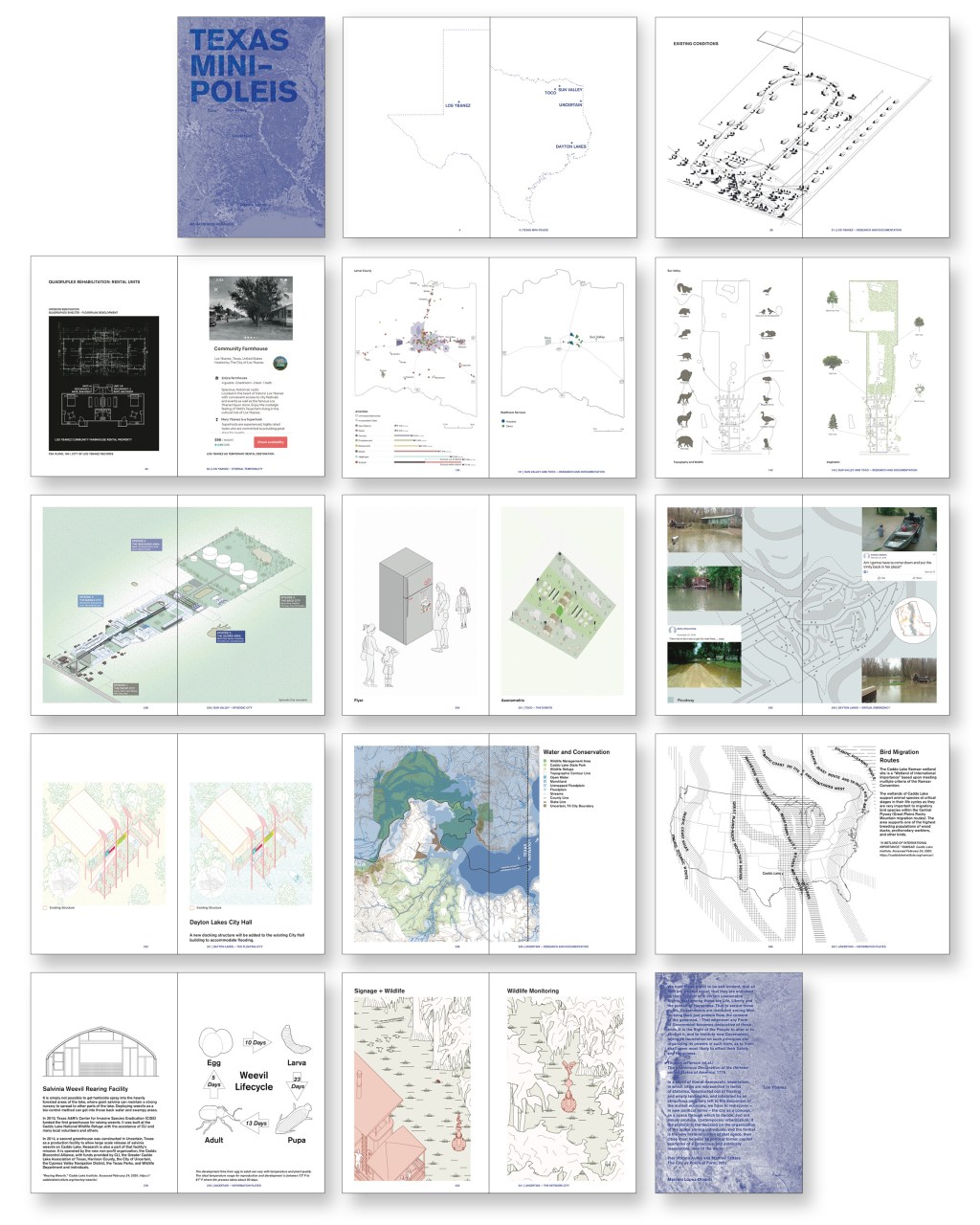

TEXAS MINI POLEIS

Everything is bigger in Texas, or not. The saying indeed reflect the vast geography of its political boundaries, yet its territory—like many others in the country’s extension, is also comprised of much smaller groupings that reflect other forms of assembly. Some of these groupings are, even in Texas, significantly small, or mini. TEXAS MINI-POLEIS is a fourth year undergraduate research-and-design architecture studio investigating Texas’ five smallest-population yet fully-incorporated cities. Although these groupings are formalized under legal statutes and incorporated as cities, their formulations reveal—and this is one of the main interests for this project, the motivations to assemble a political…

-

TABLE 3-8

-

AMERICAN ART OF THE SIXTIES

Presented the paper, Audience and Discourse: Cross-Atlantic Exchanges in the Context of the IAUS in New York City, or Inventing New Eurocentric Architecture Institutions in the 1970s during the American Art of the Sixties: Visual & Material Forms in a Transnational Context symposium held (virtual) at Texas A&M University on March 26-27 2020. Organized by Susanneh Bieber with participants across the globe. See abstracts and speakers here. Gordon Matta-Clark, Pig Roast, 1971.

-

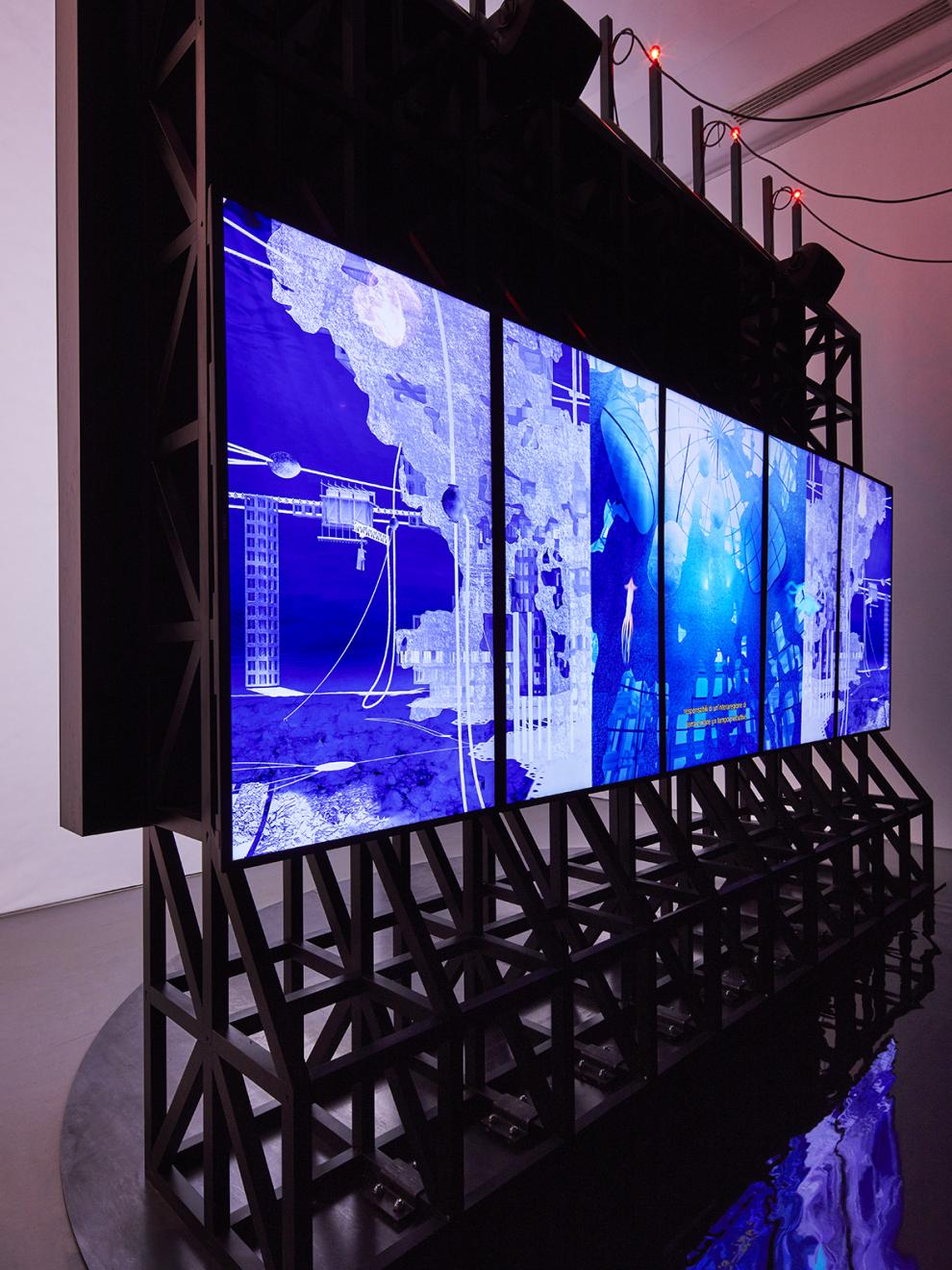

THE RISK OF NOT SPECULATING

The Risk of Not Speculating, Liam Young in Conversation with Marcelo López-Dinardi published in ARQ 102.

-

DREAMING SUMMER DESIRES BOOK

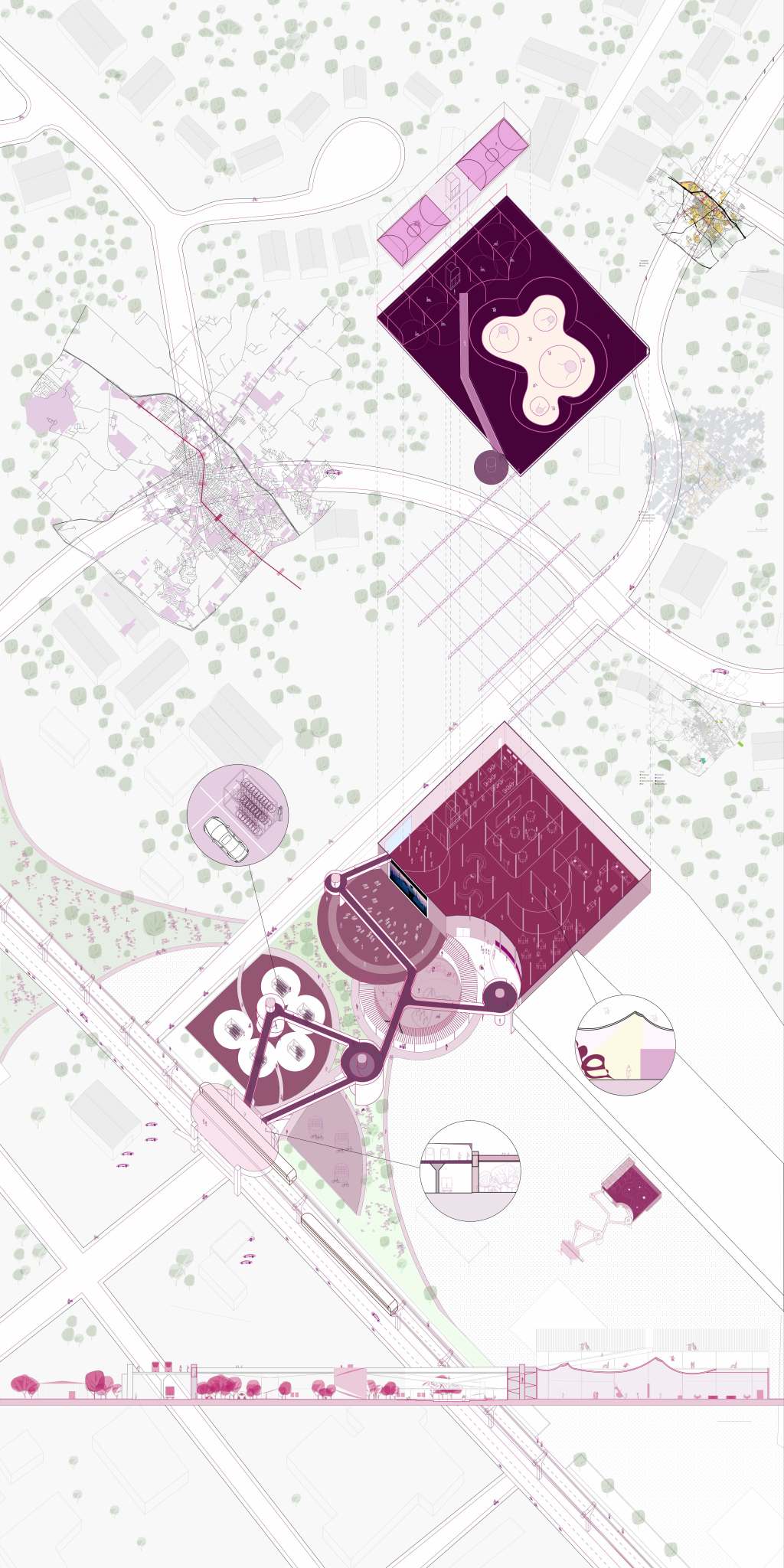

Summer intensive studio book documenting the work of the eponymous architecture studio that investigated the possibilities of play and summer desires in the context of a college town (College Station, TX) during the summer of 2019.

-

I WOULD RATHER BE___________ DREAMING SUMMER DESIRES

I WOULD RATHER BE DREAMING SUMMER DESIRES (DSD) is a project about collective imagination in a context of social and spatial dispersion. DSD departs from the premise that the city of College Station TX, is a clear evidence of the abstracted territories produced by local economies and global exploitative finance. DSD understands that bodies–humans have a subjugated role in the formal and spatial configuration of the city, designed primarily as a network of systems intending to sustain economies of extraction, profit, and multi-scale infrastructures. DSD see the city…

-

INFRASTRUCTURE, THE COMMONS AND THE RIGHT TO THE CITY

A continuation of Public Assemblies and Infrastructures from the Fall 2018, INFRASTRUCTURES, THE COMMONS, AND THE RIGHT TO THE CITY is a third year architecture studio (Spring 2019) that will consider what, how and by whom are the collective title shaped Bryan, Texas, and how their identification and critical analysis can inform the production of a program and a project for architecture in the form of a (public) infrastructure, building, public space, or a public assembly. The studio will have a strong research agenda investigating subjects, communities, legal frameworks, technology, and contemporary forms of defining the infrastructure and the commons that…

-

PUBLIC ASSEMBLIES & INFRASTRUCTURES

PUBLIC(S) ASSEMBLIES AND INFRASTRUCTURES is a third year architecture studio (Fall 2018) that will consider what and who constitutes the publics (in plural) of the cities of College Station and Bryan, in Texas, and how their identification and critical analysis can inform the production of a program and a project for architecture in the form of a public infrastructure or a public assembly. The studio will have a strong research agenda investigating subjects, communities, legal frameworks, technology, and contemporary forms of work and leisure that are informed by or resist the neoliberal logic of economical performance metrics. Finn Rotana Maclane…

-

WE CAN FIT

This short design-research projects explores alternatives for the architectural floor plan of ONE MANHATTAN SQUARE, the newest addition to NYC’s Manhattan luxury skyscrapers. The floor plan is a drawing type that can both “determine” but also “accommodate” life, it is both active form and stuff container. WE CAN FIT alters the existing plan by re-filling it with the everyday life elements that accompany NYC real-life; it speaks to the real living, the living we experience ourselves, through our friend’s stories, through Craigslist ads, all who reveal the less ideal and more fitting reality of the city. This project outcome is…

-

UNNATURAL DISASTER

The project Spatializing Debt: A Visual Audit was presented at Columbia GSAPP after an invitation by the Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture from the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation from Columbia University during the panel Unnatural Disaster: Infrastructure in Puerto Rico before, during, and after Hurricane Maria on November 9, 2018. More information about the event and its video recording can be accessed here.

-

INCUBATING

GSAPP Conversation hosted an edition with outgoing members of the Downtown NYC GSAPP Incubator at the NewInc. You can listen to it here. Participant, 2018.

-

HEADING SOUTH!

Happy to have accepted an offer to join the faculty of the Department of Architecture at Texas A&M University as Assistant Professor. See you in the south!

-

‘IN-BETWEEN THE PHYSICAL AND THE PSYCHOLOGICAL: LOCATING GORDON MATTA-CLARK AND ARCHITECTURE’ AT ACSA-MARFA

In-Between the Physical and the Psychological: Locating Gordon Matta-Clark and Architecture, is a research-paper presented during the Fall Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture–MARFA, TX conference. The paper discuss the paternal/architectural weight of the artist-trained architect Gordon Matta-Clark and his father the surrealist painter–also trained architect Roberto Matta. Examining the archive of his works at the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal it interrogates the archive as content but also as site from where to have access to his work in an anarchivic way, similar to his anarchitecture. Author, 2017.

-

GSAPP DEBATES AT IDEAS CITY NEW YORK

Architecture vs Education with Marcelo López-Dinardi and Violet Whitney, as part of the GSAPP Debates presented during Ideas City New York. Participant, 2017.

-

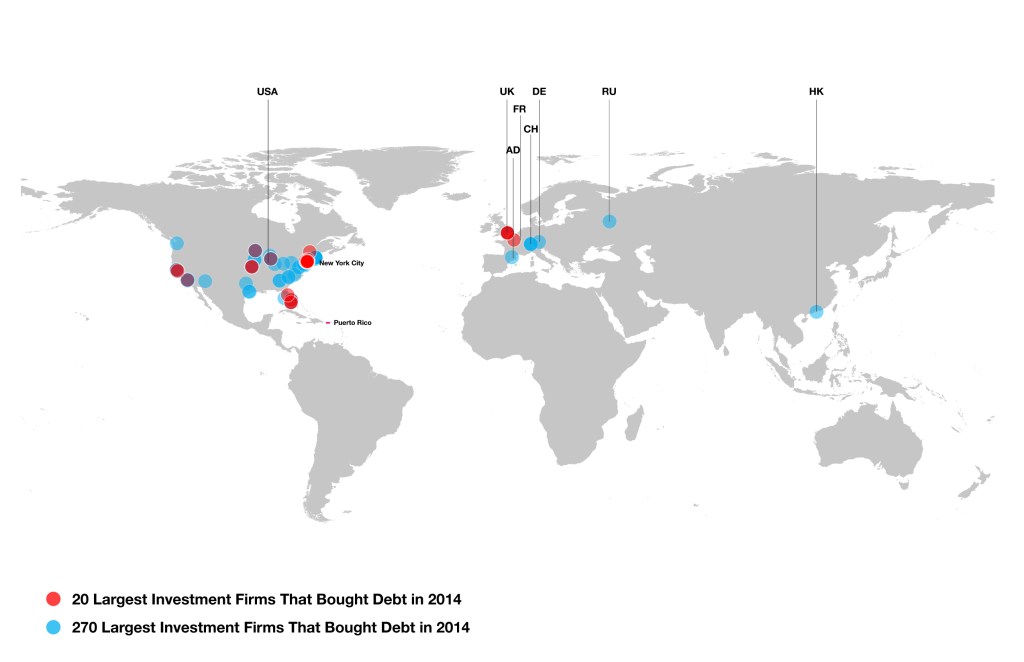

SPATIALIZING DEBT: A VISUAL AUDIT

Spatializing Debt: A Visual Auditing examines the intersection of architecture, political economy and visual imaginaries with the logics of state-financial debt under Puerto Rico’s current status, by giving territorial, spatial, and visual dimension to the so-called public debt. Investment Firms Information by the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo of Puerto Rico. Researcher, ongoing, 2017.

-

ARCHINECT FEATURE

Archinect network featured Marcelo López-Dinardi among 22 immigrants “expanding the definition of American architecture,” and feature A(n) Office in their Small Studio report. Press, 2017.

-

IDEAS CITY ARLES

Ideas City Arles was a week-long residency program organized by New York’s New Museum in collaboration with Luma Foundation (Luma Arles). “IdeasCity is a collaborative, civic, creative platform of the New Museum in New York that starts from the premise that art and culture are essential to the future vitality of cities.” Ideas City Arles considered the countryside and the challenges for a city in a “bioregion.” Fellow, 2017.

-

DOES A SURFACE SPEAK?

Does A Surface Speak? was my contribution for the collective exhibition, “Yes I’ve Had A Facelift, But Who Han’t” curated by Shyan Rahimi, Jessica Kwok and Adjustments Agency. Does A Surface Speak? is part monologue, part interrogation, part repository, and interactive piece that ask questions to the way (mostly) architectural surfaces are perceived and treated. The work engages with two forms of writing that have taken place in time over the existing walls of the former Bethlehem Church, an exceptional building within a historically contested neighborhood. One of the forms of writing is the graffiti that characterized the building before its…

-

PROMISED AIR AT MoCAD

Promised Land Air, A(n) Office’s contribution to the 2016 US Pavilion for the architecture Venice Biennale, is now on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Detroit in its first tour stop. Projects will be on display in Detroit until April 16 and will continue their tour to Los Angeles. More about the project here. Researcher, Designer, 2016. Photo Courtesy of MoCAD.

-

PUBLIC ASSEMBLIES OF WORK

PUBLIC(S) ASSEMBLIES OF WORK was a graduate architecture studio at NJIT that considers what and who constitutes the publics (in plural) of the town of Harrison, New Jersey, and how their identification and critical analysis can inform the production of a program and a project for architecture, or an assembly of work. The studio investigated subjects, communities, legal frameworks, technology and contemporary forms of work that are informed by or resist the neoliberal logic of economical performance metrics as well as our service and sharing economies. The studio was informed by various authors ideas and research about work in a our…

-

THE MEDIA OF ARCHITECTURE: PRINT, EXHIBITIONS, AND COMMUNICATIONS AT COLUMBIA GSAPP

“The Media of Architecture: Print, Exhibitions, and Communications at Columbia GSAPP” December 9, 12:30pm at GSAPP Incubator / New Inc. Rather than examine these methods within the production of architecture itself, this event explores architectural narratives as they are expressed within academic, critical, and cultural settings. We will consider the role of exhibition making, print and digital publications, as well as communications strategies with senior staff members from Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation. How might the exhibitions, events, publications, and social media content produced by an architecture school such as Columbia GSAPP provide a useful case…

-

INCUBATING NEW YORK

“Incubating New York” will take place at the GSAPP, Columbia University on December 2, 2016 at 1pm. A panel discussion about the ideas and work developed during my residency at the GSAPP Incubator between 2015-2016. More info here and video recording of the event here.

-

IDEAS CITY ATHENS

IDEAS CITY Athens was a week-long residency program organized by New York’s New Museum in collaboration with Neon Foundation. “The five-day residency will bring together emerging practitioners working at the intersection of community activism, art, design, architecture, and technology in cities around the world. IdeasCity Fellows will live and work in the Athens Conservatory and will transform the space into a multifunctional hub of cultural activity [it] will observe Athens from the perspective of two key forces that are defining cities today: the flow of humanity and the flow of capital.” Fellow, 2016.

-

US PAVILION 2016 PROMISED L-A-N-D AIR

Promised L-a-n-d Air, the A(n) Office proposal for Mexicantown/Southwest Detroit, engages the consequences of North American infrastructure for urban housing, industrial plants, international institutions, and air quality. The program for the almost 10-acre site is conceived as layers of remediation–remediating the displacement of nearby residents, remediating the proliferation of trucks in residential neighborhoods, and remediating the air pollution emitted by industry and diesel engines. Exhibited in the U.S. Pavilion for the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale. Researcher, Designer, 2016.

-

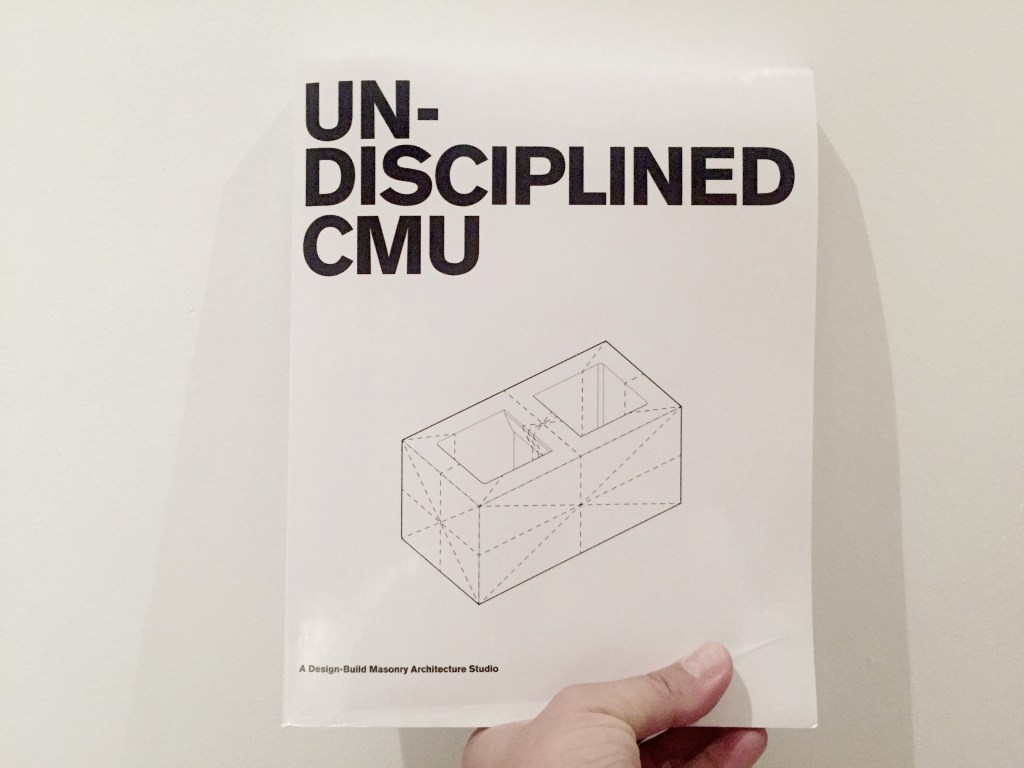

UNDISCIPLINED CMU: A DESIGN-BUILD MASONRY STUDIO

UNDISCIPLINED CMU: A DESIGN-BUILD MASONRY STUDIO is the book that document the project of the same name. The book was done during the Summer of 2015 in collaboration with Pier Paolo Pala, Chau Tran and Yuliya Veligurskaya, students who took part on the Spring semester making the project. The book is available for purchase here and to view online here. Studio Instructor, Editor, 2015.

-

UNDISCIPLINED CMU

UNDISCIPLINED CMU is the second iteration of a second year undergraduate studio project at the New Jersey Institute of Technology in which a construction is developed as part of a masonry studio. Material is investigated as a given condition and turned into an unexpected object after intense exploration. The resultant object is a concrete construction that, as an education device, opened the possibilities of reimagining and reconsidering the banality of the most typical, and less valued material in the construction industry, by literally cutting it; aiming for an expanded consideration of disciplinary knowledge and industry in the academic setting. Students: Mariza Antonio, Spoorthi Bhatta, Rawad…

-

METHODS AND MEDIA

Methods and Media is an exhibition and a lecture at the BB Gallery of the Rhode Island School of Design after an invitation by faculty members Emanuel Admassu and Aaron Forrest. Methods and Media, the exhibition, is the exploration of the unconstruction process of the A(n) Office/McEwen Studio House Opera, as I video-documented it during a single week in Detroit. The exhibition includes three 13:57 minutes films, Duration, Ascending and Rooms, and one 1:52 minutes video showing the transformed house. Each film shows a rather systematic approach to the measured capacities of the video-media, and dissects the five-days of footage, analyzing…

-

THE DAY AFTER THE CARNIVAL

The Day After the Carnival: The Hangover of Work (in Late Capitalism) was a graduate studio taught at Penn Design in the University of Pennsylvania, inquiring the intersection of work-production as a mode of carnivalesque action in the form of hangover. Students researched and draw existing program-buildings near Northern Liberties, analyzed their local-global logics, composed programmatic drawings, developed strategies and formulated and architectural assembly combining them all, including a large cultural programming. Studio Instructor, 2016.

-

HOUSE OPERA | OPERA HOUSE

The House Opera project seeks, through architectural innovation, to propose a fertile alternative to the blight binary of neglect versus demolition. The project seeks to explore what might occur when the borders of a house open up to annihilate the borders between art and community, makers and receivers of art, museums and home. House Opera | Opera House aims to open and produce new possibilities of public engagement for architecture as a discipline and for houses as a built typology, investigating the means by which a formerly vacant house may serve as a node of cultural infrastructure. As historian Reinhold…

-

URBAN_NEXT INTERVIEWS

urbanNext* conducted three interviews on my “work with A(n) Office” in Detroit, a “Designer’s Approach” and my “Curatorial Approach” for the US Pavilion for the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale. They can be accessed here. * urbanNext is an online platform aiming to generate a global network to produce content focused on rethinking architecture through the contemporary urban milieu.

-

CMU I

A complement to the 2nd year studios at the New Jersey Institute of Technology students work on a masonry build-mock-up, a competition based project in which students create a masonry construction with the help of masons, typical solid CMU blocks were cut in order to create the space of “staged interactions” within the school environment. The inquiry of the concrete masonry unit, the most typical construction element, offered the opportunity to reconsider a usually overlooked material and its capacities. First prize. Studio Instructor, 2014.

-

SYSTEMS AND TECTONICS

The core 2nd year studio at the New Jersey Institute of Technology aim to discuss and develop design strategies for the concepts of tectonics and buildings’ systems. The studio was given with an emphasis in experimenting with the tools of geometric and ordering systems and their networked capacity. Studio Instructor, 2014.

-

ARCHITECTURE OF INDUSTRIOUSNESS

Architecture of Industriousness is a short text part of House Housing: An Untimely History ofArchitecture and Real Estate in Nineteen Episodes, exhibition’s pamphlet, made for the traveling exhibition Venice’s Casa Muraro during the summer of 2014, and off-Venice Biennale site. Also available on the web at http://www.house-housing.com. Research and Production Coordinator for the Venice part of the exhibition by the Buell Center of the Study of American Architecture, 2014.

-

POST-SPECULATION ACT I

Post-Speculation Act I was an exhibition at P! Gallery featuring HOWDOYOUSAYYAMINAFRICAN. A project with A(n) Office, we designed the exhibition and installation of multimedia images and videos, as well as objects. 28 screens where displaying news and artists’ work related to urgent racial issues, subverting the typical surveillance display into a revealing and exposure device. It engaged the public audience of the street outside as well as the gallery visitors from within. Designer, 2014.

-

VISITING SPLITTING

Visiting Splitting was a film screening and conversation held around two films depicting Gordon Matta-Clark’s Splitting work, including the film Visit To Humphrey Street House, a first public screening after revealing the film from the artist’s archive. In discussion with Kelly Baum, Jessamyn Fiore, GH Hovagimyan and Mark Wigley. Event held at the Storefront for Art and Architecture. Moderator, Organizer, 2014. More info about the event, including video documentation, can be found here.

-

ANONYMOUS SYMPOSIUM

Anonymous symposium presentation on the panel Commonisms, at the Princeton University School of Architecture with A(n) Office, 2013. Video documentation of the event here.

-

LOCATING OUT-SOURCING

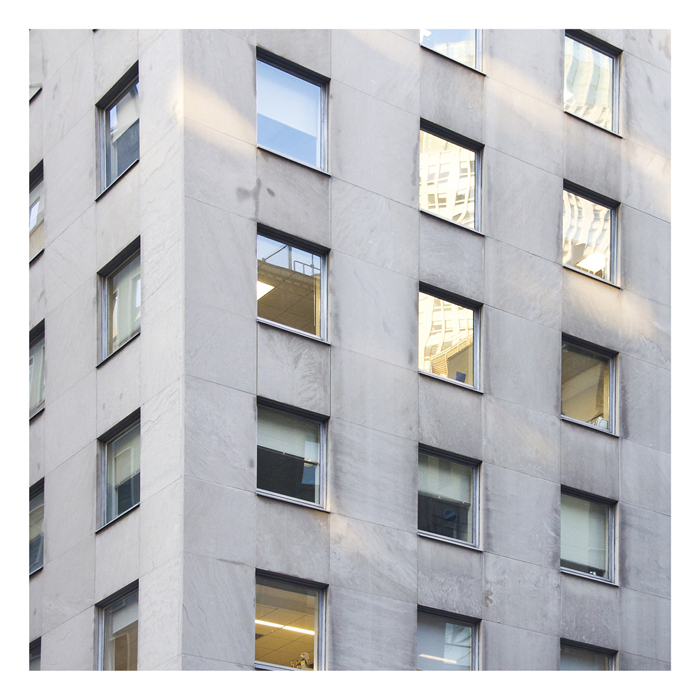

PG-Arch, a project for the exhibition Locating Out-sourcing at Studio-X Mumbai, departs from the acronyms used in the industry as a provocation for its architecture, from the Perfectly Generic Architecture (equivalent to the Professional Golf Association) to a Politically Generated Architecture. Photo shows Pangea3 headquarters, one of the largest legal-outsourcing services provider based in New York and Mumbai (photo by author, 23″x23″). Curator, Designer, Participant, 2013.

-

PROMISCUOUS ENCOUNTERS: ADRESSING/ASSESING ADHOCRACY

Promiscuous Encounters: Addressing/Assessing Adhocracy, a day-long event held at the Galata Greek School after an invitation form the curatorial team for the first Istanbul Design Biennial in November 2012, examined the exhibition ADHOCRACY curated by Joseph Grima through the lens of: invisibility, design, value and commons. Participants: Ethel Baraona Pohl, Ute Meta Bauer, Francisco Díaz, Bogachan Dundarlp, Joseph Grima, Nikolaus Hirsch, Omer Kanipak, Nina Valerie Kolowratnik, Marcelo López-Dinardi, Marina Otero-Verzier, Erhan Oze, Felicity D. Scott, Pelin Tan, Mark Wasiuta. Organizer, Moderator, 2012.

-

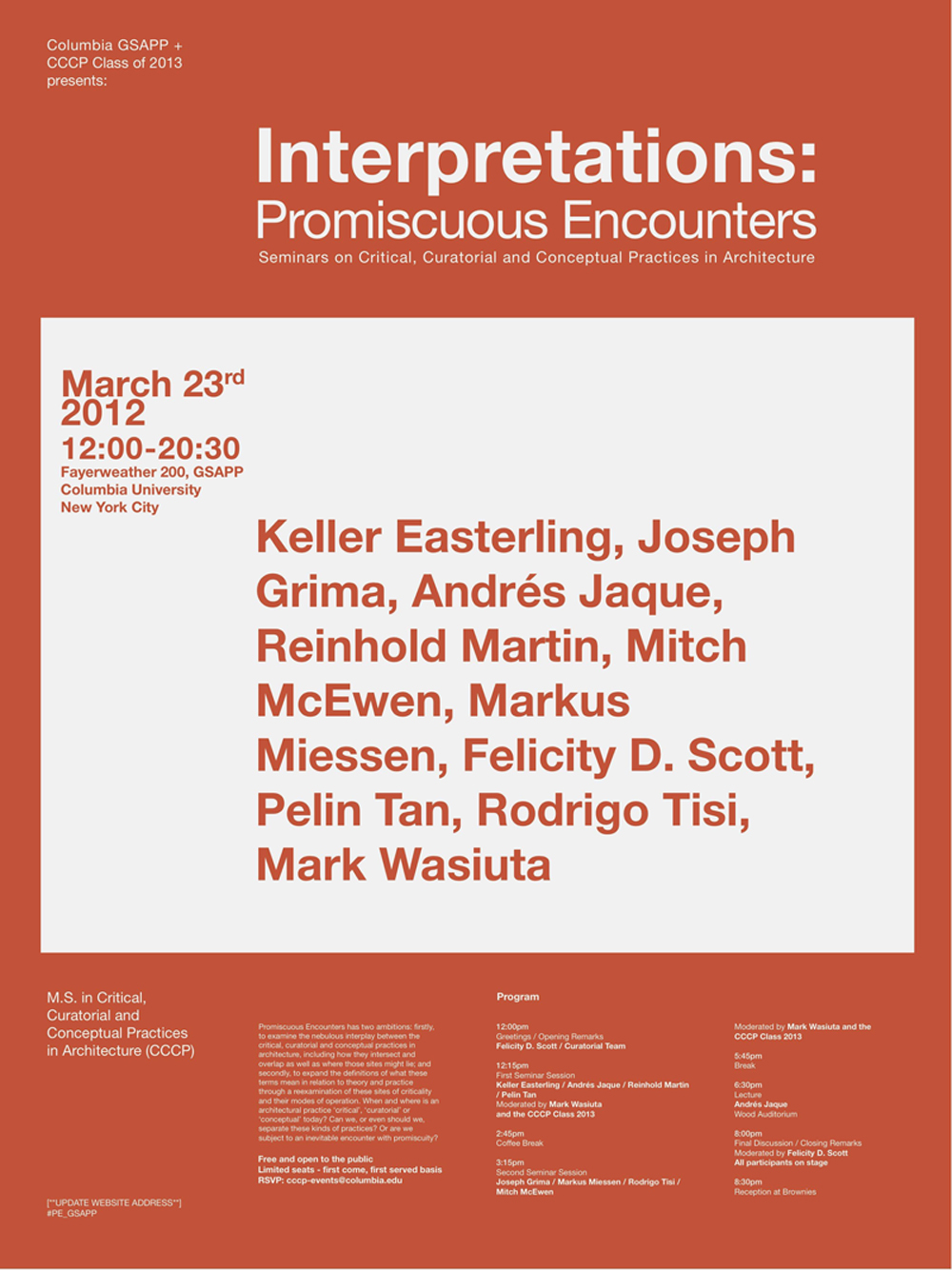

INTERPRETATIONS: PROMISCUOUS ENCOUNTERS

Interpretations: Promiscuous Encounters, a day-long event held at the Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation in March 2012, examined the interplay between the critical, curatorial, and conceptual capacities of architecture, and their promises exchanges. Neither audio nor video recordings were made. Participants: Keller Easterling, Andrés Jaque, Reinhold Martin, Mitch McEwen, Markus Miessen, Felicity D. Scott, Pelin Tan, Rodrigo Tisi, and Mark Wasiuta. Curated by: Francisco Díaz, Nina Valerie Kolowratnik, Marcelo López-Dinardi, Marina Otero-Verzier.

-

CIUDADLAB: BRAZIL, THE FORM OF DESIRE

After researching the cities of Rio de Janeiro, Brasilia and São Paulo in Brazil we identified leisure, void, security, industry, body, tourism and monumentality as drivers of the forms of desire. With and ever expanding economy, Brazil has become the world’s eighth economy and the destination for countless local and international events. The research was organized through three analytical lenses -the Imagined City, the Ideological City and the Informal City- and worked with the hypothesis that in Brazil the imaginary of desire is employed to promulgate the worshipping of the body, the architectural object and the staging of both within…

-

POLIMORFO

Polimorfo is the journal of the School of Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico. Founder, Editor, Designer, 2009-2011 (in collaboration with Oscar Oliver-Didier). PDF available online here.

-

SENSE RECESSION: WHAT COMES NEXT?

Sense Recession: What Comes Next? was a lecture series inquiring and exploring architectural practices as they emerged or were formulated out of the financial crash (not crisis) of 2008. Invited Lecturers: Xavi Sempere – Culdesac, Spain; José Luis Vallejo & Belinda Tato, Ecosistema Urbano, Spain; Giancarlo Mazzanti – Colombia; Carmina Sánchez del Valle, Hampton University, USA; Sabine Müller – SMAQ, Germany; Mitch McEwen – SUPERFRONT, USA. Lecture Series Director, School of Architecture, Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico, 2009-2010. (Complete lecture series text below) We are reaching the end of the 21st century’s first decade and it would seem that architecture…

-

CIUDADLAB: UTOPIA IN MOSCOW

As with every CIUDADLAB research and exhibition project, we pick a different destination in an attempt to broaden the frame of reference from which we imagine the city. During the year 2008, choosing Moscow seemed to sense Russia’s renewed presence in the geopolitical game as we experienced the beginning of a renewed “Cold War.” Beyond Moscow’s exoticism with respect to a Western minded group, three theoretical frameworks established possible lines of comparison and analysis: Imagined City, Ideological City and Unfinished City. Through site visits, documentation and interviews, we looked to a heavily ideological city, and the traces of an unfinished imaginary world. The clash…

-

CIUDADLAB

A research and exhibition driven platform for examining and revealing the critical and emergent issues formulating the contemporary production of cities. We investigate cities across the world always identifying pressing issues of their role within a local or global scenario; social and economical inequality, migration, urban imaginaries, urban growth, geography, power, surveillance, biopolitics and memory have been critical themes in previous projects. For more information you can download a complete pamphlet here: ciudadlab-pamphlet-web For online videos of the various projects visit our Vimeo page here. Founder-Director, 2004-present (in collaboration with Oscar Oliver-Didier).

-

ROUNDTABLE SERIES

The Roundtable Discussion Series began as a complement to the first CIUDADLAB course offered at ArqPoli in 2005. The conversations were conducted with the idea of bringing to the school multi-disciplinary issues pertinent to our discipline. The invited panelists came from a wide spectrum and fields, provoking more than mere conversations, but vivid debates that nurtured the students’ concerns and understanding of the career’s scope. – Suburban City: Mutation and Variation of the Dispersed Model – Method, Concept, Matter: the Re-education of Architecture – Leisure and Business: the New Geographies of Public Space – The Neoliberal Landscape: the Territory Economics…

-

FLMM NEW VISITORS CENTER

The project, the new Visitors Center and Museum for the Luis Muñoz Marín Foundation in San Juan, Puerto Rico, situates itself as a mediator and threshold between a large semi-urban forest and a historic site grouping the former home and small buildings of the owners, where the house of the first elected governor of Puerto Rico is located. A bold two-pieces volume resembles and occupied the space of a natural border that existed before, while providing a threshold welcoming flows through the building to the site and the forest. View it published in Divisare and ArchDaily. Project Lead Designer for Toro Ferrer Arquitectos, 2006-2013. AIA…

-

PLACE AND CONTEXT STUDIO

For the initial part of the course, first year undergraduate students where confronted to notions of place and context. An analytical city study was developed through the layering of cartographic drawings including a vast variety of the city’s visible and invisible infrastructure. Mixed media, hand drawn. Studio Instructor, 2007.

-

HOUSE O

The house was conceived as a large open interior/exterior space in between the front and back gardens of the elongated site. Two less permeable volumes contain the private and support areas. Formal public living areas are covered with a high roof to create a continuous environment with the gardens and outdoors. Project Lead Designer for Toro Ferrer Arquitectos, Lead Project Manager and Construction Administrator, 2006-2011.

-

ANARCHIST GARDENER

Led by pedestrian deity (Finnish architect Marco Casagrande), the anarchist gardener performance developed 12 “industrial zen gardens” during a 9 hour walking performance between the cities of Bayamón and San Juan. The anarchist gardener aimed for a better pedestrian city lost to vehicles. Performance, 2003.

-

ABOUT

Marcelo López-Dinardi is an Associate Professor of architecture at Texas A&M University. His work explores architecture’s entanglements with culture. He is the editor of Architecture from Public to Commons (Routledge, 2023) and Degrowth (ARQ, 2022), and co-editor of Promiscuous Encounters (GSAPP Books, 2013). López-Dinardi’s words and works have been featured in the JUMEX Museum, MoCAD, Istanbul Design Biennial, Citygroup, Storefront for Art and Architecture, Old Armory of the Spanish Navy of Puerto Rico’s National Gallery, MAC-PR, CAAPPR, The Avery Review, The Architect’s Newspaper, Domus, Art Forum, URBAN_NEXT, PLAT, ARQ, Materia, and Bitácora Arquitectura. López-Dinardi is 2025-26 TAMU Melbern G. Glasscock Humanities Research Center Fellow elected to…

-

CONTACT

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.